This week we’re going to look back at one of my comic book projects.

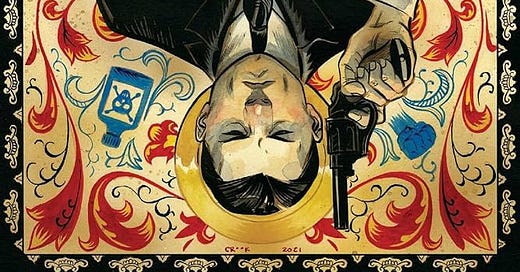

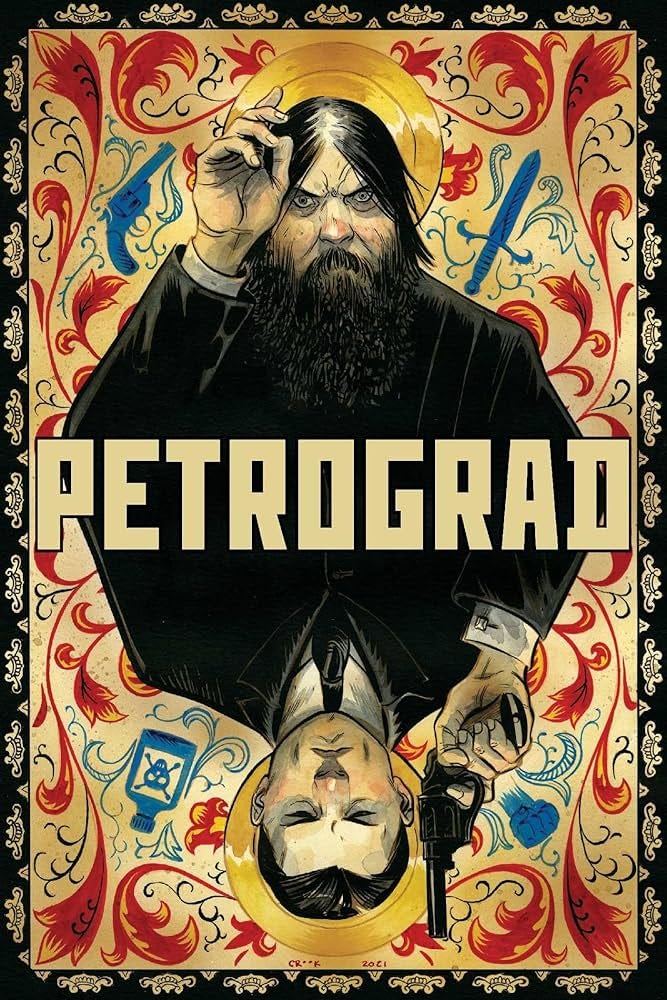

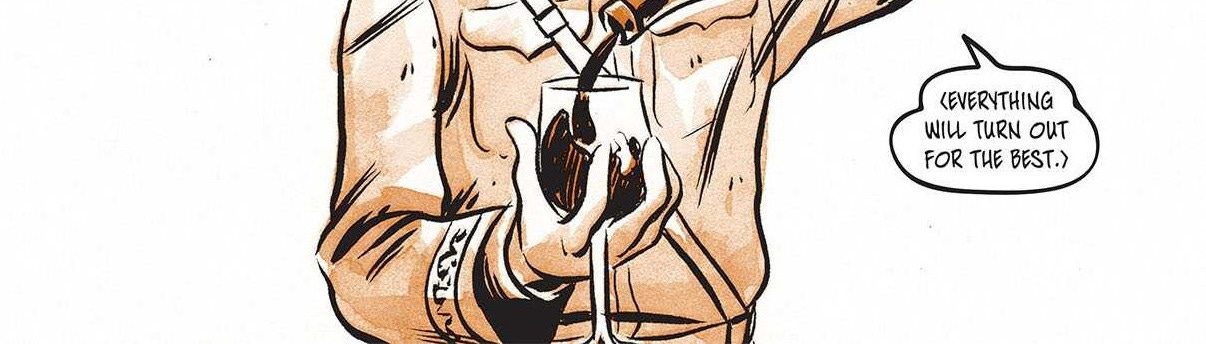

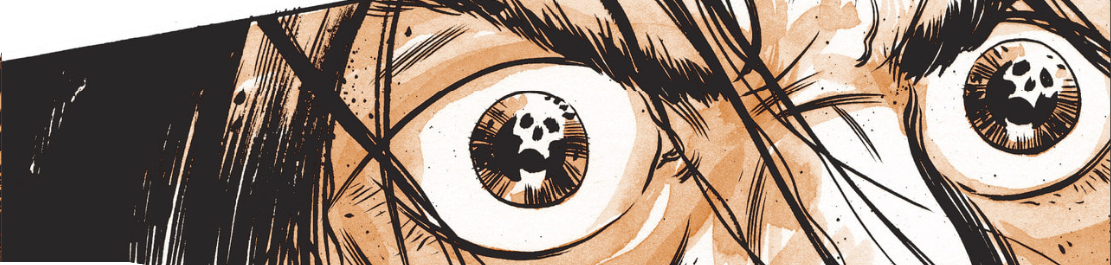

Published by Oni Press, with art by the incredible Tyler Crook, Petrograd tells the story of the assassination of Rasputin as a spy story.

We’ve been talking about science-fiction and horror… time to mess around with some historical fiction.

A Spy Story

Based on the theory that that assassination was committed with aid from the British government, Petrograd tells the story of this most infamous of murders as if it were a spy story.

The theory goes that the British heard that Rasputin was pushing the Tsar and Tsarina to make a separate peace with Germany. Had that happened, the British and French forces on the Western front would have been overwhelmed by the redirected German forces.

And so the, theory posits, they moved against Rasputin.

There is some evidence this is true. But the question of its veracity didn’t matter so much to me. It was just too strong a hook of a story. I felt I had to do something with it.

For this project I decided that I wanted to be as historically accurate as I possibly could be. With one exception. I wanted to have my own, invented spy character at the heart of it.

Cleary is the name of that spy.

The book then concerns all of the things you’d want a spy story in 1916 to concern. International intrigue. Secret police. War. Nascent revolution. The doomed Russian royals.

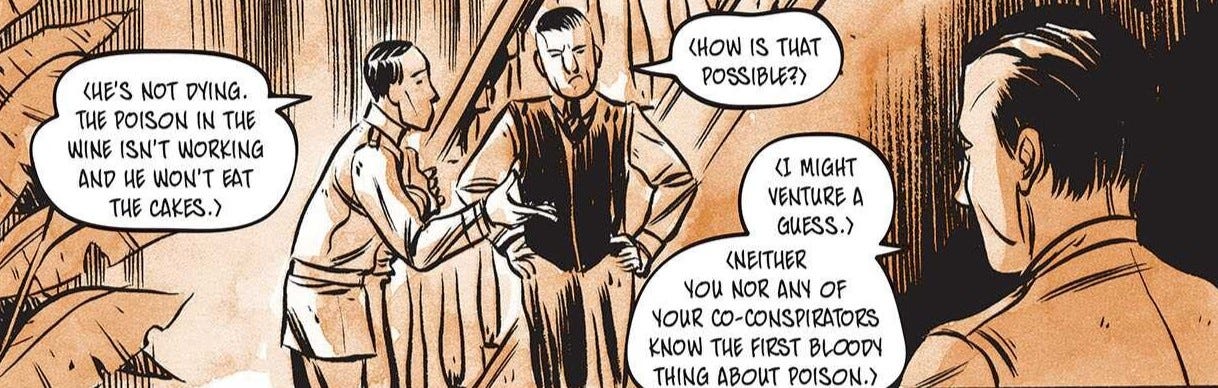

And, of course, its marquee set piece would be that most infamous of assassinations, played for maximum suspense with just a dash of horror.

But Also Not Really a Spy Story

But just to return to Cleary for a moment.

It seems, honestly, that I can’t really engage with a genre unless I’m trying to mess with it somehow.

And so I constructed him purposely as a kind of anti-James Bond figure. Not a man of action. No great charm. Not even a man of great courage or conviction. Just a person who finds himself at an extraordinary moment of history and has to decide how to act.

The story begins with Cleary already in Petrograd having gotten into the intelligence service to avoid serving at the front.

Buried in Cleary’s backstory is that he’s Irish born. And that country’ struggles against the English, and his non-involvement in it, weighs heavily on everything that happens in the book.

It’s through Cleary that I wanted to make a spy story that was infected with other flavors. There’s a certain slice-of-life feel to the book; there’s also a certain feeling drudgery, that this spy work is still work.

And then when the conspiracy takes off, there’s a certain sense that it gets immediately beyond Cleary’s control. He’s not a mastermind, he’s not a great tactical mind, he’s not even good with a gun.

He’s a bit like a character in a Coen brother’s film. In way over his head, as events (some of his own making, others not at all) come rushing at him.

In that sense, readers were meant to feel like they were in Cleary’s shoes.

Reilly

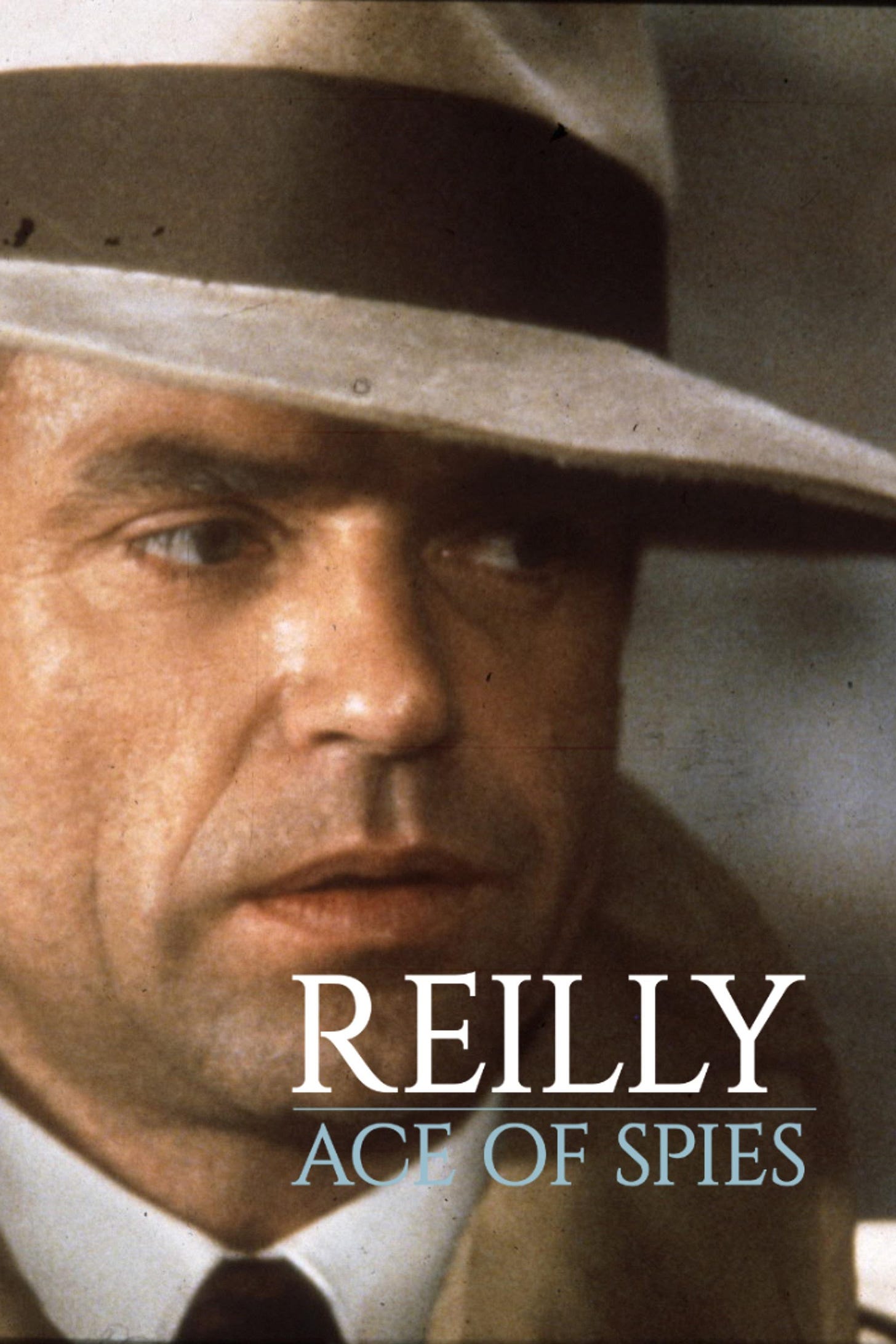

The central inspiration for the book was the 1983 British produced series “Reilly: Ace of Spies.”

The series starred Sam Neill as Sydney Reilly, a real historical figure operating in and around Russia from the late 1890s up to his execution by the Soviets in 1925. Reilly’s exploits are the kinds of things one reads about and thinks “that can’t possibly be real history.” He’s a figure well worth reading about for anyone with an even passing interest in early 20th century history, spy stories, the Russian Revolution, or frankly just fascinating shit.

The series is sunk in a deep, intriguing, morass of gray morality. Reilly himself is an unsettling figure. The viewer’s never really allowed to feel at ease with him or his motivations even when his actions are the stuff of a proper spy story.

He’s hero and villain. A self-serving altruist. Complicated and ambiguous and impossible to really pin down. Just like history itself. Just like most people.

And Neill as Reilly is fantastic.

It makes an incredibly strong case for him as the best of all once possible James Bonds. If you haven’t seen it, here’s his screen test for the role.

Obviously, I love James Bond. But if push came to shove, if I had to choose I prefer my spy-stories le Carré flavored. Complicated, guilt-ridden, ambiguous, and soul-cold.

The Bridge

One of the great things about genre as a concept is that if you can get the reader to buy in, you then get to see what you can get away with.

So what was I trying to get away with in Petrograd?

I never likes to explicitly say what I think the subtext of any thing I write is. I’d like to think readers will find it for themselves.

But of Petrograd I will say I was trying to tell a spy story that evoked a certain set of feelings.

Among those: the feeling of trying to stay out of the spotlight but failing… the feeling of having friends who constantly drag you in deeper than you care to be… the feeling of a plan going horribly off the rails…

And the big one: the feeling of waking up one morning and realizing that history isn’t over. That in fact, the opposite is true. You exist in history. You’re living it and it’s happening right now whether you like it or not.

The feeling, the sudden ice cold bath sensation, of realizing that the decisions you make, what you decide to do or not to do… it all matters.

And one more too. The dark, hidden side of that feeling of self-determination. The feeling that having acted with the very best of intentions, having chosen your side, and taken your actions, that in the end, despite all of that… maybe everything we do comes to nothing. And the very best we get is that we’ll never know.

Y’know. Spy story stuff.

You can pick the book up here. Or from your local library.

And be sure to read everything else Tyler’s done. In particular look for The Lonesome Hunters. He wrote and drew it. It’s a stunner. His work never disappoints.